History of Rochester, NY: How Industry Shaped the City’s Growth

Rochester has always been a city built by water, wheels, and willpower. From its earliest days, settlers harnessed the Genesee River’s power and attracted industrious minds. Over time, flour mills gave way to seed companies, then cameras, optics, and tech ventures. Each wave of industry left a fingerprint on neighborhoods, institutions, and the city’s pulse.

Rochester NY history is more than headlines or museums — it’s the story of reinvention. When you walk past a converted mill or drive past Kodak Tower, you are moving through decades of ambition, hard work, and change.

Founding on the Falls: Water Power and Early Settlement (1810s–1830s)

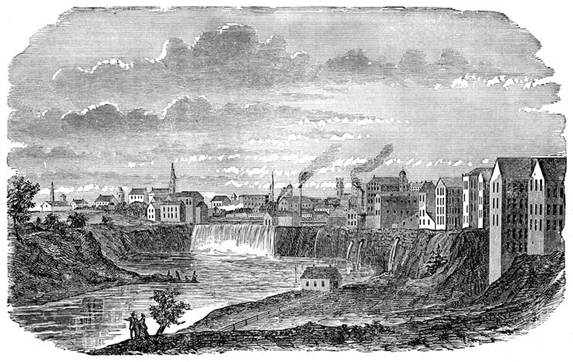

In the early 1800s, settlers recognized a rare advantage: the High Falls on the Genesee River. That drop created strong water power, enough to drive mills. Rochester’s first flour mills sprang up there, drawing farmers, laborers, and capital. The stretch of river became the backbone of the city’s mechanical heart. Flour milling quickly earned Rochester the nickname “Flour City.” As local farmers brought grain from surrounding counties, mills processed it at the falls. The dense concentration of mills around the riverbanks created not just jobs, but a living, breathing industrial core.

Canal construction and water access amplified that growth. Once waterways and river rights were secured, entrepreneurs built sawmills, gristmills, and ancillary businesses. Settlers found that proximity to water meant energy, shipping, and a built-in market. The early pattern of industrial clusters near the Genesee’s power set a template: industry near energy, housing nearby, and associated services clustering around.

The Erie Canal and the Rise of Commerce (1820s–1850s)

When the Erie Canal opened, Rochester’s geography turned into a strategic hub. The canal linked Albany and Buffalo, creating an internal highway that redefined trade in upstate New York. Rochester quickly became a node in a vast trade network. Goods flowed in and out. Millers shipped flour eastward. Supplies moved west. Warehouse districts grew along the water and canal banks.

Population responded. Merchants arrived. Transport firms set up offices and crews. Housing sprouted for laborers, sailors, and clerks. The canal allowed Rochester to punch above its weight. Where before it relied on local agriculture and milling, now it anchored commerce between coasts. Rochester trade history in this period is a story of lift—the canal lifting local firms to regional significance. The city’s layout reflected it: canals, docks, storage buildings, and streets radiating outward.

From Flour to Flowers: Industrial Diversification (1850s–1890s)

By mid‑century, wheat yields in the region had plateaued, and competition grew stiffer. Rochester’s leaders looked for the next engine. One path lay in horticulture. Nurseries and seed companies blossomed in and around the city. The nickname “Flower City” emerged as plant nurseries like Ellwanger & Barry introduced innovation in breeding and landscaping. Ellwanger & Barry shaped both the economy and the city’s parks, cemeteries, and boulevards.

Industry diversification spread outward. Manufacturers turned to machinery for nurseries, packaging for seeds, and glasshouses. The industrial character of the city broadened. The same spirit that drove flour milling found new directions. Rochester horticultural history became a natural companion to the milling era. Neighborhoods adapted, with nursery owners, gardeners, and laborers contributing to a more varied industrial base.

Photography and Innovation: The Kodak Era (1880s–1930s)

Then came George Eastman. In the 1880s he founded what became Eastman Kodak in Rochester. He saw photography not as a luxury but as a mass product. His vision brought new chemical processes, film, and camera design to a city already accustomed to mechanical enterprise. Kodak became a mass employer. Jobs ranged from chemistry and optics labs to factory assembly lines.

Kodak helped define what middle-class life looked like in Rochester. For generations, gaining a stable job at Kodak meant a steady income, benefits, and pride. The company’s global reach elevated Rochester’s reputation. But more than that, Eastman’s example fostered a culture of innovation. Optical engineering, lens work, chemical R&D, those fields spread into spin‑offs and supporting firms. Kodak history in Rochester is thus central to the city’s identity as a place of technical creativity.

The Power of Education and Engineering

Industry needed talent. Rochester answered. The University of Rochester and Rochester Institute of Technology grew as more than schools. They became bridges between the factory floor and the research lab. RIT’s technical programs supplied engineers, draftsmen, and machinists. The university sponsored research in chemistry, optics, and medicine. Together, those institutions kept feeding industry with new skills and fresh ideas.

These education hubs helped firms adopt more advanced methods. A hardware manufacturer might tap faculty research; a startup could draw interns or partner for labs. Education became a backbone of industrial renewal. The presence of those institutions also drew families to settle near campuses, influencing residential patterns, commercial zones, and entire neighborhoods tied to academic life.

The Manufacturing Boom: Precision and Production (1930s–1950s)

The mid‑20th century saw Rochester at its industrial high point. Bausch + Lomb grew as a world leader in optics and lenses. Gleason Works became known for precision tooling and gears. Xerox (then Haloid) evolved into a leader in office technology. The city’s reputation for exacting craft and mechanical complexity became a defining trait.

This era transformed migration into the city. Workers from rural areas, immigrants, and people from other states poured in seeking factory positions. Housing filled out around mills and plants. New neighborhoods rose to serve those communities. The industrial strength of this boom shaped where people lived, how they commuted, and what businesses followed them—cafes, shops, transport.

Labor, Diversity, and the Social Fabric

With factories came a workforce from near and far. African Americans migrating from the South, European immigrants, and later waves from other nations joined the ranks. Ethnic neighborhoods coalesced—communities with their own churches, shops, languages, and traditions. Union activism became central: workers pressed for safer conditions, wages, benefits. Strikes and labor disputes shaped political dynamics. Industrial labor built opportunity, but it also reinforced inequality—the disparity between executives and assembly workers, between neighborhoods with amenities and those without.

Working‑class neighborhoods defined much of the city’s character. Streets lined with modest houses, small yards, local stores sprang up near plants. Over time, some of these areas became doses of industrial decline too. But the social fabric woven during the boom era remained visible: in churches, schools, social clubs, and community identity.

Postwar Prosperity and Suburban Expansion (1950s–1970s)

After World War II, the country embraced the automobile and highways. Rochester was no exception. New roads and improved infrastructure encouraged suburban growth. Industry followed. Kodak Park expanded. Corporate campuses and suburban plants appeared in towns like Greece and Henrietta. Rochester suburban growth took shape: towns once rural became industrial satellites.

Population spread outward. Workers no longer needed to live right next to plants. Suburban office parks, housing developments, shopping centers—all emerged. Some downtown and inner‑city areas began to lose density. But infrastructure investments of this era (roads, bridges, sewer systems) cemented the new shape of the region. Corporations could draw from a broader labor pool; employees could choose to live in quieter suburbs yet commute to manufacturing.

Deindustrialization and Economic Transition (1980s–2000s)

By the 1980s, the industrial winds shifted. Kodak, Xerox, and Bausch + Lomb faced global competition, automation, and changing markets. Layoffs, plant closures, and corporate restructuring followed. The shock was severe. Downtown factories sat idle. Unemployment spiked. Neighborhoods that depended on a single employer struggled to adapt.

Civic leaders stepped in. Industrial zones lost to blight were rezoned. Brownfield lands were cleaned up. Old mills became lofts or studios. City officials and universities partnered to attract new sectors. The post‑industrial economy of Rochester began to emerge. The scars of decline remained, but so did hope. The narrative shifted: how to turn old manufacturing power into future opportunity.

Reinvention Through Technology and Small Enterprise (2000s–Present)

Rochester built on its technical legacy. Startups in optics, imaging, software, and photonics gained traction. Organizations like NextCorps provided incubation, mentoring, and funding. The Downtown Innovation Zone (DIZ) emerged to cluster entrepreneurs near academic and cultural anchors. The city’s old factories and mills found new life: coworking spaces, art studios, food halls.

Adaptive reuse projects bridged past and future. Historic mills now house small firms. The Public Market sits in a building with deep roots. These sites respect industrial architecture while promoting 21st‑century ventures. Rochester innovation economy grows not in spite of its history but because of it. The bridge between old engineering and new tech feels natural here.

How Industry Still Shapes the City Today

Though many factories have shuttered, industrial heritage remains visible in Rochester’s layout, architecture, and identity. Kodak Tower dominates the skyline. Repurposed mills along the Genesee and former canal banks host offices, housing, tech firms. Historic districts cling to their industrial aesthetic: brick, heavy timber, large windows. Historical buildings like The Powers Building now host some of the best personal injury firms in Rochester. The city’s innovation DNA flows through sectors like photonics, biotech, and renewable energy — fields that echo Rochester’s optical and manufacturing strengths.

Rochester industrial legacy is alive. The same engineering mindset that drove lens factories and precision tools now powers startup labs and manufacturing prototypes. In each new facility or reclaimed warehouse, you can see an arc: flour → flowers → film → tech. That trajectory still guides growth, zoning decisions, and city identity.

The City That Builds Itself

Rochester is more than a backdrop, it’s a living testament to industry’s ability to shape place, people, and purpose. Every era left visible traces in the architecture, roads, and neighborhoods. The mills, canals, corporate towers, and startup labs all tell parts of the same story. The inventive energy that built the Flour City still pulses through Rochester today. Historic societies, local museums, and walking tours help keep these layers alive; visiting them is a way to see where the city has been and where it might go.

What Sets Us Apart From The Rest?

Horn Wright, LLP is here to help you get the results you need with a team you can trust.

-

Client-Focused ApproachWe’re a client-centered, results-oriented firm. When you work with us, you can have confidence we’ll put your best interests at the forefront of your case – it’s that simple.

-

Creative & Innovative Solutions

No two cases are the same, and neither are their solutions. Our attorneys provide creative points of view to yield exemplary results.

-

Experienced Attorneys

We have a team of trusted and respected attorneys to ensure your case is matched with the best attorney possible.

-

Driven By Justice

The core of our legal practice is our commitment to obtaining justice for those who have been wronged and need a powerful voice.